Tech

Two per cylinder, or four… or what about seven or eight? 40 years after the revolutionary Yamaha FZ750, Jamie Turner explores the reason behind its five-valve layout and explains why everything now has four…

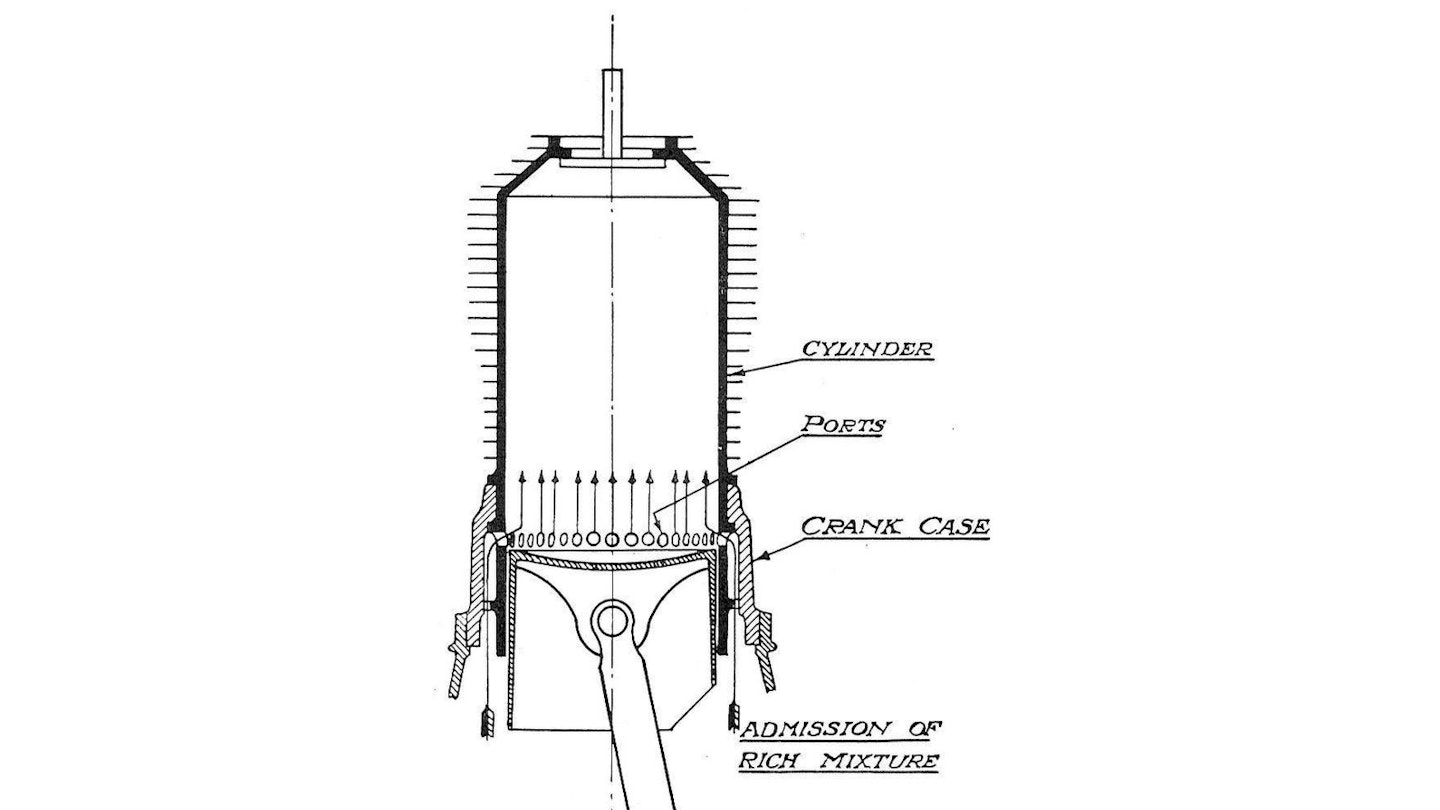

Now there’s a question. We could go down a massive rabbit hole of alternative valve concepts, but let’s restrict our ruminations to poppet-valve arrangements. Obviously, if you’re a two-stroke fan you could argue that ‘none’ is the answer, but I can think of two-stroke engines with up to four, with some of the most remarkable having just one, for the exhaust in ship engines. They’re super, super efficient, but not particularly practical to put in a bike frame.

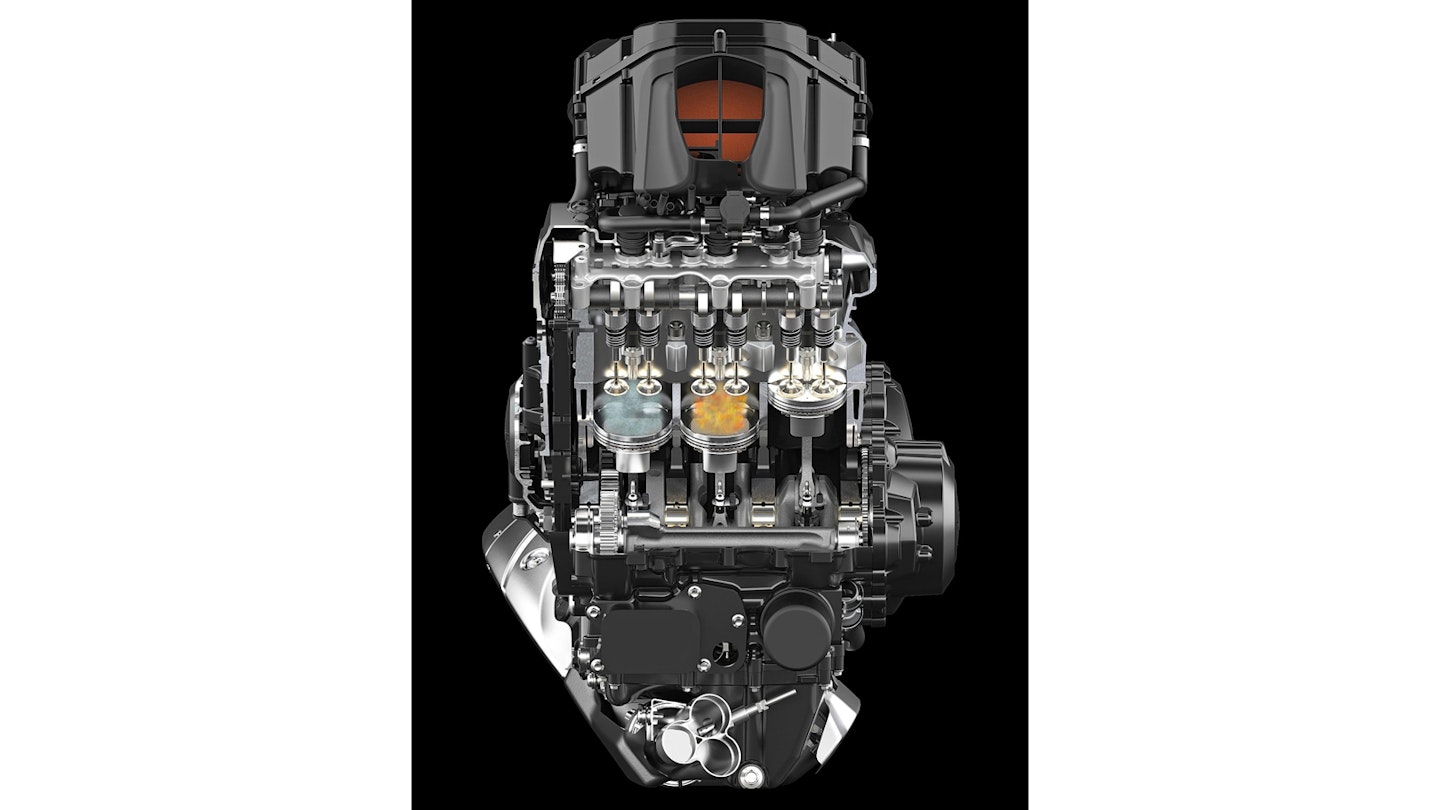

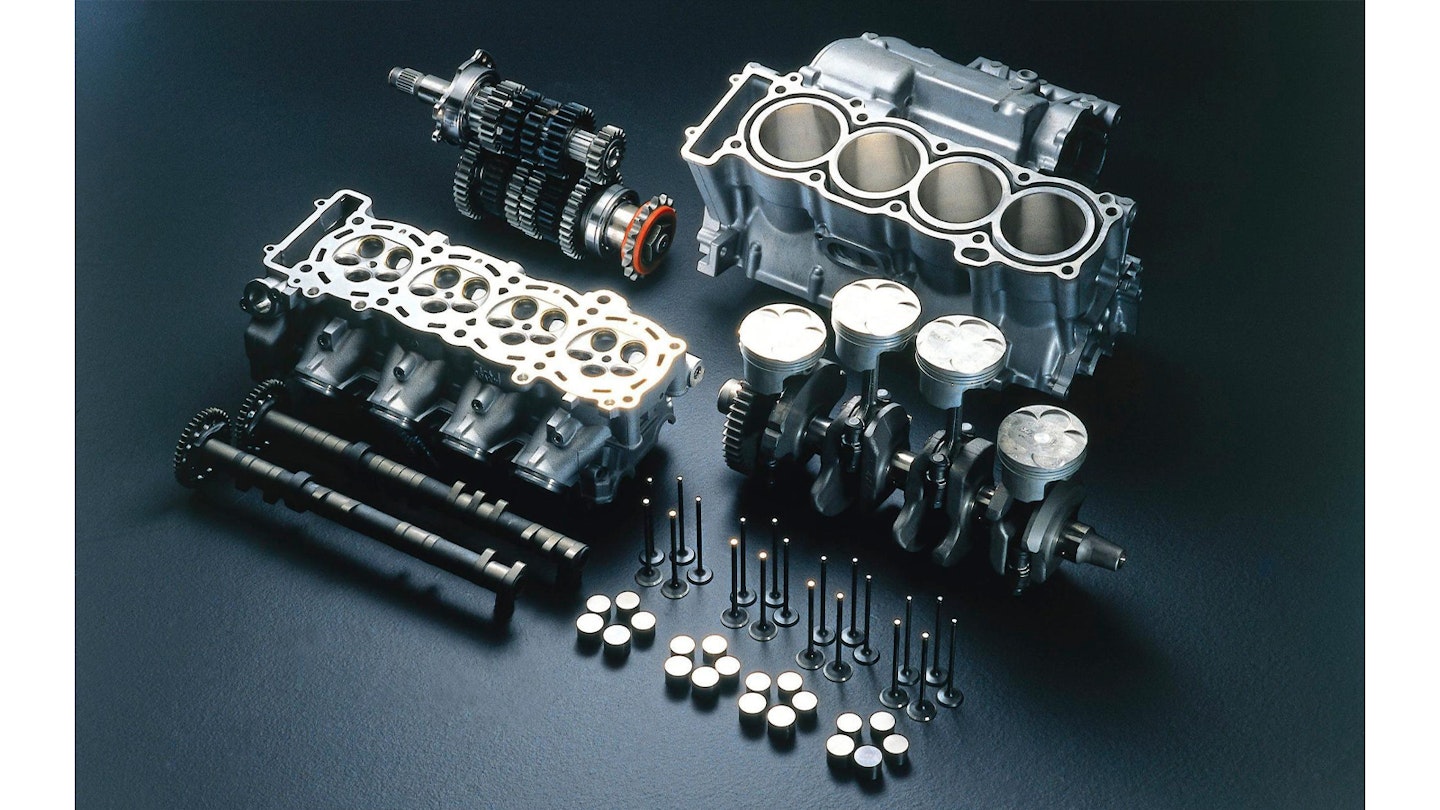

So, let’s just think about four-strokes, where any number of valves from one to eight have been tried. (Yes, one. The French ‘Monosoupape’ or ‘single-valve’ had a single exhaust valve and piston intake ports – weird in today’s context but interesting in its own way. I can feel another rabbit hole opening up…) While I think we know the answer now, it was not ever thus. Two is clearly the minimum number for separated intake and exhaust functions and using two gives the manufacturer lots of choices of how it lays its combustion chamber out. The best is hemispherical, though even that is quite a complex arrangement requiring rockers – think Ducati – or twin camshafts. The hemi also lends itself to twin spark plugs, helping combustion a lot, but most are single spark. Now, the valves in a hemi are big, and inclined at a wide angle, meaning that engine speed is quite limited by valve kinematics (even if you are Ducati and use desmodromics) and the total flow becomes limited earlier by the ‘curtain area’. This is the area between the valve head perimeter and its seat that the air actually flows through. When the valve has lifted to about 30% of its diameter, the restriction swaps to become the port area – meaning that to increase the flow area, effectively you need to increase the area of the valves. And – bingo! – the reason for wanting to investigate configurations with many more valves… From the practical minimum of two, people have increased to three (with twin valves for either inlet or exhaust), four (obviously), and onwards up to eight. Four is where things really click: you get the benefit of lighter valves on the intake and exhaust, so engine speed can be high; the intake port is an excellent shape for tumble flow, which we now know is what you want in a four-stroke spark-ignition engine (although you’ll take any air motion you can get at part load); and finally, the combustion chamber is compact with quite a lot of freedom on valve angles. Flatter is generally better – I always associate this with Cosworth – and wanting lower included valve angles was fundamental in Ducati moving from the Desmoquattro to Testastretta arrangement. Two exhaust valves aren’t really needed for flow reasons, but they do give a large amount of valve perimeter for better exhaust valve cooling. Crucially, the spark plug is in the middle, meaning the shortest possible flame path for good combustion and knock control.

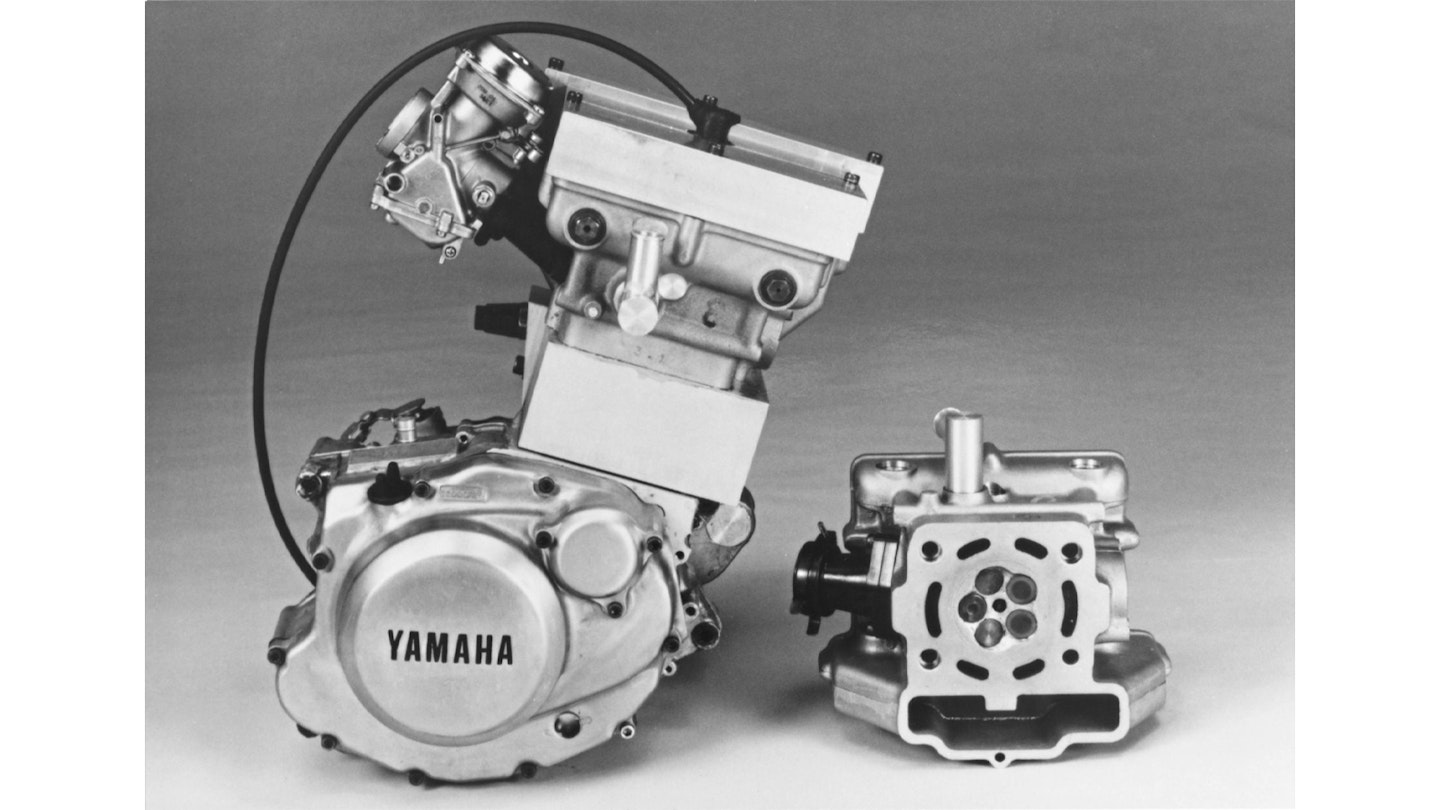

All of this is why, once it started being adopted, the four-valve-per-cylinder (or 4vpc) juggernaut quickly took the world by storm. But once 4vpc had achieved a critical mass, engine engineers, being inquisitive types, started to wonder whether there was another ‘next level’ layout: if four was so good, surely more would be better, wouldn’t they? And so the stage was set for much weirdness. In a bike context, perhaps the most successful of the ‘higher’ numbers of valves is Yamaha’s 5vpc design, produced in great numbers starting with the FZ750 (see p24). However, it took them a while to decide on that. They looked at 5vpc, 6vpc, and 7vpc, against the backdrop of wondering whether a four-stroke could compete with two-strokes in Grand Prix. A full 7vpc 500cc V4 was built and tested, producing 125bhp – quite the output when it was shown in 1980. Staggeringly, it had a bore of 70mm and a stroke of 32.4mm for a bore

While they built and ran the 7vpc configuration, they also investigated 6vpc on the way (with different numbers of inlets and exhausts and either single or twin spark plugs), and of course, 5vpc. There is stuff online about these remarkable creations, but Yamaha also wrote a technical paper (SAE 860032, if you have a mind to look it up). If you are cynical this was perhaps to justify the company choosing 5vpc over 4vpc in the FZ750, but it does compare flow areas for four to seven valves. Shocker, in that paper the 5vpc arrangement comes out the best and 4vpc the worst. Hmm.

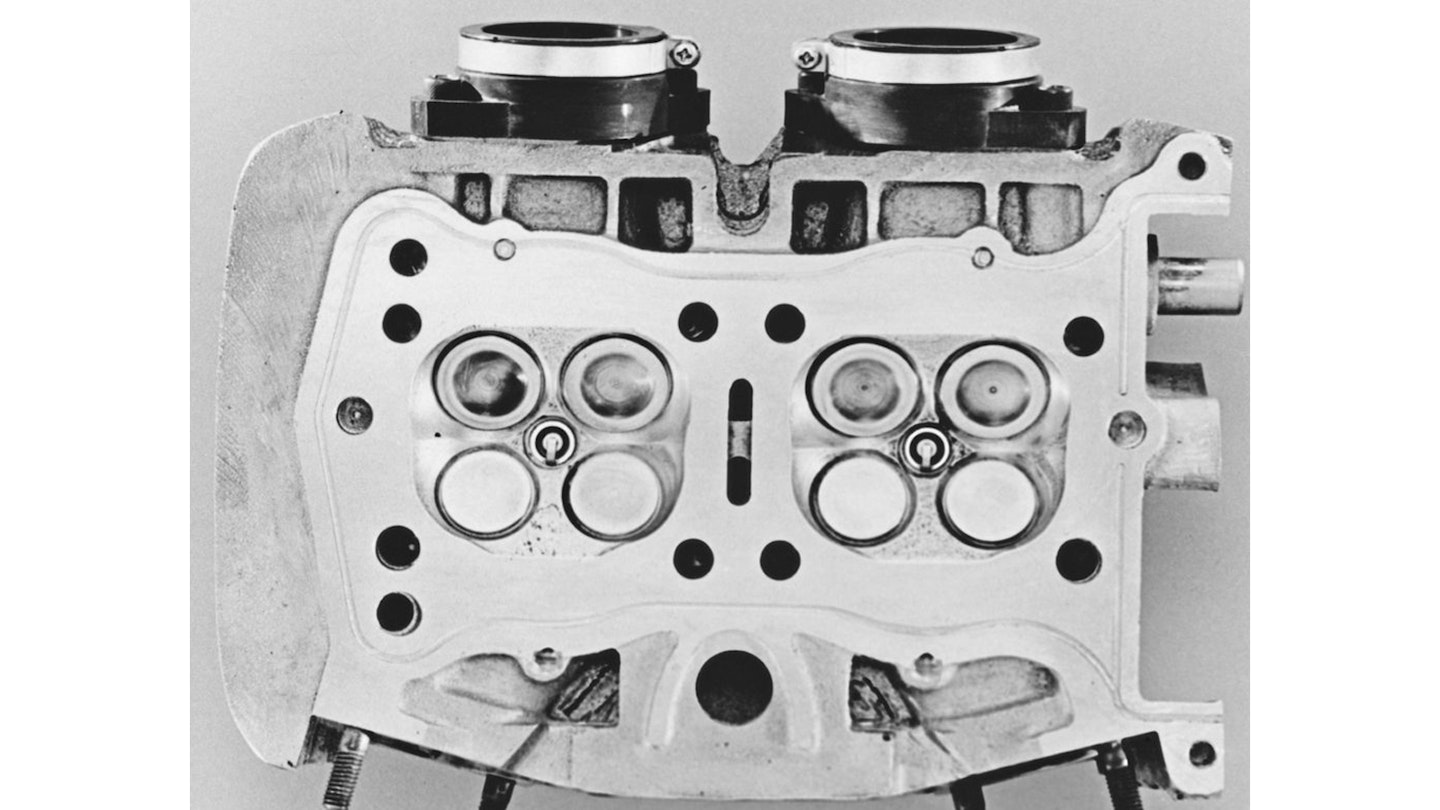

Now, driving the valves is obviously a challenge to meet. And the effects of this are where it starts to become seriously unravelled, in my opinion. If you use two cams and direct drive, then for 5vpc you are going to have to position the valve stems at angles so that one of the intake valve heads is ‘flatter’ than the other two, which just looks plain odd (I have no idea what they did with the 6vpc and 7vpc). In the 5vpc this gives a pretty sub-optimal combustion chamber with lots of squish (popular back then, but it promotes heat loss) and one valve has a worse port shape that leads to masking by the bore wall, which adds to the interference in air flow between the valves in general.

Long story short, it was very difficult back then to make a call between four and five valves, although there is the fact that 5vpc obviously costs more due to more parts and machining. Ferrari and Audi both productionized 5vpc engines, and Ferrari ran 5vpc V12s in F1 for a long time (Maserati showed a 6vpc concept as well, but by then in the car world I think everyone thought that was a marketing gimmick). Audi apparently had a nightmare with thermomechanical stresses due to cooling – hence my comment for the 7vpc in that respect. Ultimately, everyone went back to 4vpc, and I think that decision is now reinforced by the more recent development of direct injection, which also makes a claim on cylinder head real estate and cooling. For Yamaha, that just left the business of justifying the volte-face, but I guess they somehow got away with that…

So, 4vpc is clearly best; it also allows the (almost) ready application of radial valves if you want to, further improving combustion chamber shape. Still, we must applaud Yamaha’s lateral thinking. However, history suggests they just weren’t thinking laterally enough – which brings us to the only eight valve I know of, the Honda NR ‘oval piston’ engine.

If you check the definition of ‘cylinder’ you’ll find that – for all that we think they must be round – they don’t have to be. They can be any prismatic shape, Spam tin included. Honda realised this and – given the 500cc Grand Prix limit of four cylinders – essentially took a V8 design and siamesed adjacent pairs of cylinders together. Truly, this was an elegant exercise in rational unorthodoxy, spurred on Yamaha’s work into 7vpc, and actually worked very well – or did once they had ironed out the bugs, which sadly came too late for its racing career. (Again, if you have the inclination, check out another paper – SAE 930224.) One of the key enabling technologies in the end was the manufacture of piston rings with internal springing (this is when the pistons went truly oval, rather than racetrack-shaped with two parallel sides); while that doesn’t seem very exciting, it shows that sometimes you have to solve some odd problems to make a technology work. But let’s not forget – fundamentally they took two 4vpc cylinders and siamesed them. Four valves was still the optimum… So, four valves per cylinder currently rules. And to me, it’s a great example of the old engineering truism, ‘if it looks right, it is right’. But don’t think it’s anything but old. Look at a Napier Lion W12 from 1916. It has 4vpc, twin overhead cams, and a single cam cover – all the architectural ingredients of a ‘modern’ engine. Truly, there is nothing new under the sun…

Jamie Turner is Professor of Engines at KAUST. He owns a BMW K1200S, a neat GSX-R125 and loves two-strokes.