Tech

Today’s bikes are capable of mileages our forefathers would have deemed impossible – and we have two rather unexpected things to thank…

By Jamie Turner

As children, most of us were told that two wrongs don’t make a right. But for bikers two things that can make our noses wrinkle – cars and exhaust emissions – can, it turns out, make things good for us. They’re the primary reason why bikes don’t break and do massive mileages.

Clean air is what we all want and need. Worldwide there’s been progressive tightening of emissions limits in this regard for many years, with the first regulations raised in California in 1966 due to ever-worsening air quality. The car industry, of course, fought back in their normal way by claiming there was no real way of meeting the regulations and it would bankrupt them. They squealed and squealed until it was obvious The Man wasn’t going to back down, then met the rules after all. However, the cost in good ol’ American hosspower was monumental. ‘Derated’ doesn’t even begin to cover it. ‘Eviscerated’ would be closer.

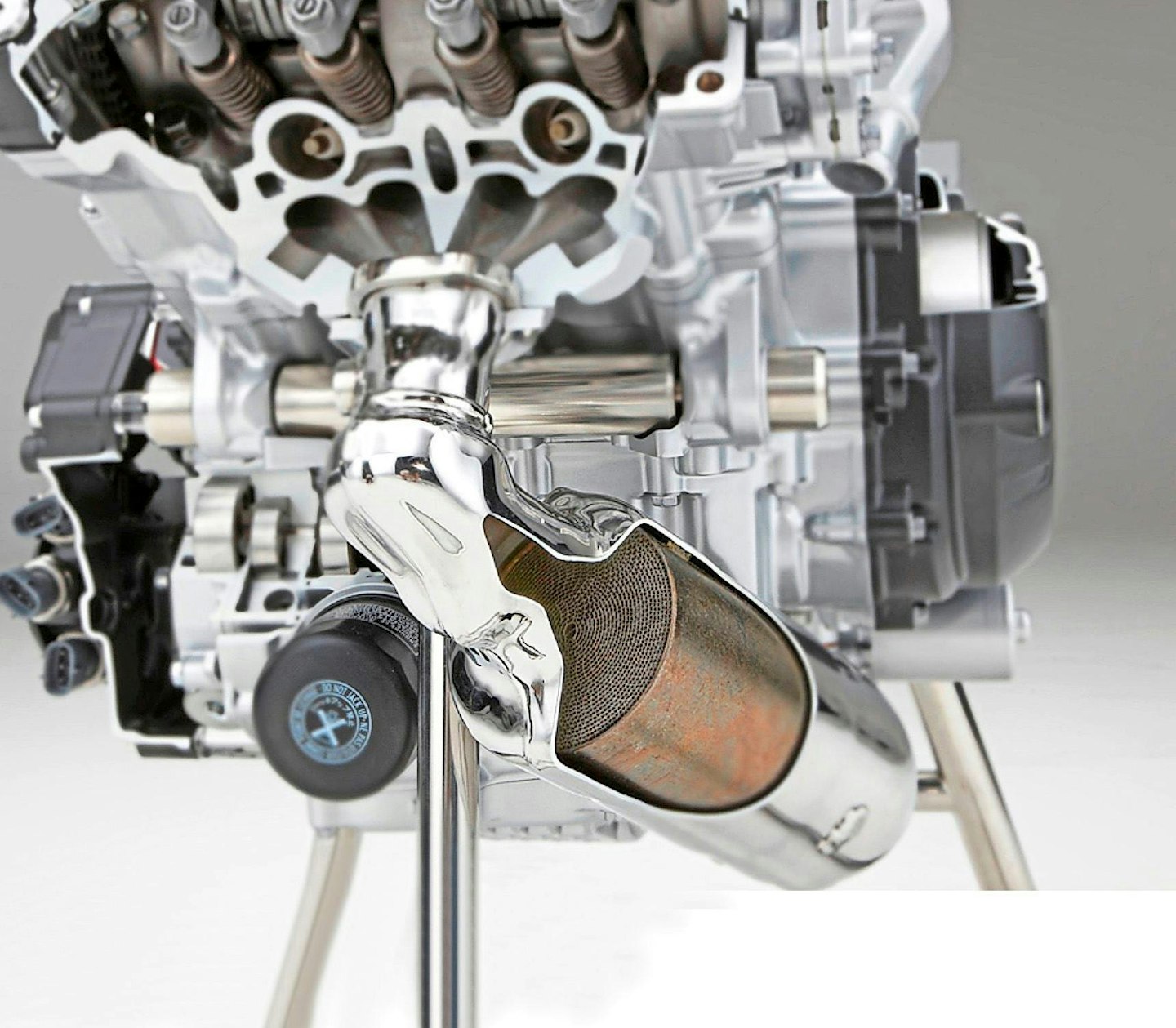

In 1973 the first automotive catalytic converter was produced, enabling a massive step forward in emissions control. The first ones were simple ‘two-way’ jobs that only converted hydrocarbon (HC) and carbon monoxide (CO) emissions, but they did allow tuning options that the previous best technology – thermal reactors, basically big empty boxes in the exhaust that kept gases hot for as long as possible in the hope HCs and CO would miraculously disappear – could not. Oxides of nitrogen (NOx) were later dealt with in a two-stage catalyst system where the engine was run slightly rich to reduce the NOx using some of the HC and CO in a first cat, with what was left of those then being oxidised in a second one after air had been squirted in by a pump. Complex, but it worked. Then it was realised that with sufficiently accurate control of the air/fuel ratio a single cat could do the job, and so one of the most fantastic devices ever was invented: the three-way cat (TWC).

Call me sad, but the TWC is a stupendous piece of kit. In this smallpackage all the hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms magically get rearranged to produce just nitrogen, water and carbon dioxide. Once it is ‘lit’ this happens with 99.99 per cent efficiency as exhaust gases fly through. There is absolutely no doubt it saved the spark-ignition engine.

Anyway. When cats were introduced, engines were down on pre-regs outputs, but it was obvious it was a device that could massively reduce emissions. Obvious to all, including legislators. The stage was thus set to keep ratcheting down emissions limits, and to require compliance over ever ‐longer mileages. And to keep increasing requirements to a level that would have been impossible beforehand, while monitoring things over longer periods. Naturally, this gave rise to evermore powerful engine control systems (fuel injection, electronic throttles, variable timing – you name it).

As an example of increasing requirements, for cars we have to show emissions compliance for over 150,000 miles. On-board diagnostics have been mandated in the US and Europe so that sensors continually diagnose whether other sensors are working properly, and if not the dreaded malfunction indicator lamp (MIL) is thrown. Any problems have to be reported. In the US, if your product shows a tendency to fall out of compliance the Environmental Protection Agency can force you to recall and fix them. Every. Single. One. Through MIL lamp reporting the agency also noticed that, in general, cars had a tendency to show problems with their emissions systems after someone had spannered them badly, so they made it illegal to require any maintenance to anything in the ‘air path’ (from air filter outlet to catalyst system outlet). Except the spark plugs, which I always think is weird. This included cam drives and boosting devices. Both had to take a massive leap in durability as a result.

Other things were needed. Oil consumption had to be nailed because of HC emissions, so understanding of piston/liner dynamics had to be improved. Friction had to be reduced because burning more fuel inherently leads to more emissions (we really had to do this for CO2 emissions reduction, but it’s true for criteria pollutants, too).

‘Next time you smell clean air, remember achieving it has been good in more ways than one’

It’s all harder with direct injection (DI) and we haven’t mentioned particulate emissions. But you can see that, due to technologies developed and deployed because of emissions regs, the modern engine is an astounding achievement. At modern emissions levels it cleans the air; it’s way cleaner than cigarettes, barbecues, or cooking your Sunday lunch; it’s more efficient and powerful than ever; it’s super-driveable even with ridiculous power; it’s durable like you wouldn’t believe; and it’s convenient and cheap, providing great utility – in exactly the way that a battery electric vehicle doesn’t.

If you’ve got this far, you’ll be asking what on earth this has to do with motorcycles. They’re not subject to the same emissions limits – either in absolute terms or monitoring. The fact is that bike and car manufacturers share the same suppliers and consultants, their engineers move between them, and they use the same processes and tools to develop and make their products. Consequently, the whole ecosystem just improved massively. Bikes just couldn’t help but get better as well.

When I was a greenhorn engine development engineer at Norton and Lotus, I used to bemoan evermore difficult emissions targets. Then an experienced old hand said to me: ‘No, lad, you’ve got it wrong. Meeting these limits is bloody hard. And bloody hard means more people are employed for longer…’ Ever since I’ve said bring it on. Effectively the only limit we cannot achieve cost-effectively is zero. So they can ban the engine – that’s exactly what the politicians have set for tailpipe CO2 . Given the historical efforts of all those super ‐clever engine engineers, that’s hardly fair, is it? Especially when it’s the fuel that’s the problem, not the engine per se.

All that said, I find myself horribly conflicted on one thing. Emissions regulations have taken something big from the biking world – the two-stroke engine. However, this was mainly down to the type of stroker that we had grown to love: the crankcase-compression type. We could now fairly readily meet bike emissions levels with a two-stroke using things like DI, stepped pistons (as used on the Wulf engine), and variable compression ratio (easy-peasy with a two-stroke – just see the Lotus ‘Omnivore’ which used it to be able to consume pretty much anything). In these challenging times no one is going to invest in that sort of thing. Or will they? Hope springs eternal…

So, there you have it. Meeting ever-decreasing limits over longer distances and continual snooping by the vehicle controller itself has made everything super-reliable and durable over pretty enormous mileages. Everything had to step up. It’s been improving steadily and quickly over the past few decades, and the result for every vehicle fitted with an engine has been remarkable. Next time you are out for a ride smelling the clean air, remember that achieving it has been good for us in more ways than one.